Making a rhythm game (part 1)

May 2022

Few months back I got into osu!catch (also known as CTB / Catch The Beat). I was also studying IT at school at that time, which meant I was frequently bored and had nothing to do, only having access to my school-provided chromebook. That’s when I got the idea to make a web version of CTB so I could play that instead of reading yet another isekai manga on my phone for hours on end.

During this time I was still very much into Rust (still am) so I decided to write the game in it. Rust supports cross-compiling to WASM which is a type of assembly language as an alternative to javascript, all major browsers support it. One of the few game frameworks that supports WASM target is Macroquad. Its API is based on raylib which means you just have to write a small infinite loop and put your game logic and draw code in there and then calling next_frame().await at the end. Please don’t skip over the code section, spent a few seconds reading it, it’s not as hard as it looks.

use macroquad::prelude::*;

#[macroquad::main("BasicShapes")]

async fn main() {

loop {

clear_background(RED);

draw_line(40.0, 40.0, 100.0, 200.0, 15.0, BLUE);

draw_rectangle(screen_width() / 2.0 - 60.0, 100.0, 120.0, 60.0, GREEN);

draw_circle(screen_width() - 30.0, screen_height() - 30.0, 15.0, YELLOW);

draw_text("IT WORKS!", 20.0, 20.0, 30.0, DARKGRAY);

next_frame().await

}

}

If you’re wondering about what this async and await stuff is and how it works I recommend this blog post by fasterthanlime. It goes into detail how futures and polling works in Rust. But in short it’s a requirement when running code on web. Macroquad also has a short explanation in its README.

Audio

I got some basic graphics running but I quickly ran into issues when implementing music playback. Its audio playback system wasn’t adequate enough for my use case. One of the major features lacking was a way to get the current position of the playing sound, which is essential for a well-synced rhythm game.

I don’t plan to get too much into the details but basically to calculate accuracy and draw notes at the correct position you need to know how much time has passed. Measuring the time manually or updating the position incrementally almost guarantees that graphics and audio will become desynced. Audio thread can lag a little while the update thread doesn’t, and vice versa.

What I ended up doing was using Kira to handle my audio instead. Kira provides this function which was perfect but I still have issues with it not updating as frequently as it should, I even poked around the source code but couldn’t figure anything out. It performs a store to an AtomicU64 (bit-casted to f64) very frequently but when the main thread performs a load it doesn’t get updated, I’d need to read up more on atomics to determine any solution to it. I’ve also thought of moving to cpal and writing something more optimized to audio latency but it’d be too much work for now and I don’t know much about audio programming either.

It’s not only important that the audio is synced but also that it’s smoothly updated. What I ended up doing to get around the infrequent audio position updates was making a sort of interpolation or “prediction” as I like to call it. Every time I receive a new time position from Kira, I will set the “predicted time” variable to what it reports, which is normal.

if delta != 0.0 {

self.data.predicted_time.set(time);

}

self.data.predicted_time is the predicted time variable I referred to. This variable is what is used when drawing graphics. time here refers to the time reported by Kira. delta is the difference from what Kira reported last frame and what it reported this frame. If this is not 0, that means the value reported this frame is different from last frame.

If delta was 0, that means Kira didn’t report a new position which means, I’ll have to predict what it should be. I add the time it took for the last frame (which is when the last audio position was reported).

if delta == 0. {

self.data.predicted_time.set(self.data.predicted_time.get() + get_frame_time());

}

As I said before, timing yourself easily causes desync but since we use Kira’s audio position to anchor it every few frames, it won’t get cause any large desyncs. That is unless get_frame_time() gets very large or Kira updates slowly…

Hints

First, if the computer isn't powerful, it'll lag, causing low FPS, which means large frame time and secondly; web doesn't have the greatest audio system. Did I mention I wanted to play this on a cheap chromebook?This is how drawing the falling fruit looks like by the way (slightly simplified).

// Get the y position of the fruit as a function of audio time and fruit time.

let y = self.fruit_y(self.predicted_time, fruit.time);

draw_texture_ex(

// Texture

data.fruit,

// X Position

self.playfield_to_screen_x(fruit.position) - radius,

// Y Position

y - radius,

// Color Tint

if fruit.hyper.is_some() { RED } else { WHITE },

// Additional Parameters

DrawTextureParams {

// Size of the texture as it appears on the screen

dest_size: Some(vec2(radius * 2., radius * 2.))

}

);

This is actually the only place in the entire game that predicted_time is used. For calculating hitboxes and accuracy I use the time reported by Kira. This is for greater consistency and to not break replays, online scores among other things. I didn’t mention it until now but I also added replays and online ranking.

Non-blocking Gameplay

Although Macroquad forces you to use async and awaits everywhere that doesn’t mean the gameplay isn’t blocked. Look at this code for example

async fn update() {

// Await stops execution of the function and returns to the caller.

load_music().await;

if button.clicked() {

do_something();

}

}

If you call load_music and then await it, the execution will stop which means the if case for checking button interaction never gets executed. The whole game will become unresponsive during any awaits. But unlike other languages, the only way to progress the asyncronous function is to constantly poll it, which is what Macroquad does.. at the top level. We need a way to poll futures without stopping the world.

Introducing.. A custom future executor! Also known as the “promise executor” as a reference to JavaScript’s Promise

// Variable `loading_promise` of type `Promise<(SoundData, Image)>`.

let loading_promise: Promise<(SoundData, Image)> = promise_executor.spawn(async move {

// Load chart music.

let sound = data

.audio_cache

.get_sound(&format!("resources/{}/audio.wav", title),data.main_track.id())

.await

.unwrap();

// And then load background image.

let background = data

.image_cache

.get_texture(&format!("resources/{}/bg.png",title))

.await;

// A statement without a ; means return in Rust. We return a tuple containing the music and background.

(sound, background)

});

// This line executes right after constructing the promise

do_stuff();

/* ... */

let (sound, background) = promise_executor.try_get(&loading_promise).unwrap();

Warning: This is where it gets pretty technical, you may want to skip this part.

The Promise Executor

Futures (async code) has to be polled to progress, what happened to that? Well, the promise executor doesn’t poll it automatically but instead exposes a poll method on itself that will go through the stored promises and poll their futures. In CTB-Web this is done at the start of the update loop like this self.data.promises().poll();. Here the self.data.promises() part returns a &PromiseExecutor, a reference to a PromiseExecutor which then gets .poll() called on it.

If you check the documentation for Future you’ll notice it actually has a poll function, why don’t we use that directly? If you take an even closer look at it you will see the poll method signature looks like this.

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output>;

Not very pleasant to work with, it’s actually quite hard to create the correct types to call this. PromiseExecutor is basically a wrapper that hides all the complexity of calling it. Also note, Future is a trait, not a struct like Promise, which makes it harder to store. Let’s take a look at how Promise is defined.

pub struct Promise<T> {

cancelled_or_finished: Cell<bool>,

id: slotmap::DefaultKey,

_phantom: PhantomData<T>,

}

Ignoring PhantomData<T> (it’s required because of Rust stuff), it contains a cancelled_or_finished which is currently not used for anything other than debugging purposes, and it contains id stored as a key to a generational vector. In short, it’s a safer index to a dynamic array. Promise

The actual stuff is contained inside the PromiseExecutor. When you spawn a future, it will add it to a list, which it later uses to go through and poll.

self.promises.insert(FutureOrValue::Future(Box::pin(async {

Box::new(fut.await) as Box<dyn Any>

})))

fut is a future that returns something. Rust requires all types in a vector to be of the same type, but we want promises that return wildly different things so what do we do? We cast it to something called dyn Any which is a type that contains something that implements Any (which every type does). dyn Any is unsized which means it can be of varying size because it can contain different structs, getting to the same problem that Rust wants everything to be the same in a vector, type and size alike. Box is a pointer, when it’s no longer used, the pointer gets free’d. A pointer is of a known size so that means Box<dyn Any> is a type that can store anything. This is why I added T to Promise<T> so we can cast back from Box<dyn Any> after the promise has been polled to completion.

fut.await returns T. Box::new(fut.await) will construct a Box<T> which we then cast to a Box<dyn Any>. We wrap this inside an async {} block to make this bit of code async so we can call await. The async block will create a Future<Output = Box<dyn Any>>, a Future that returns anything. Like I said before, Future is a Trait, in reality, the async {} block returns an anonymous type that implements Future, which we can’t name nor store properly in a vector. So we have to do the same thing again, wrap it in a Box! The final type will be Box<dyn Future<Output = Box<dyn Any>>> but that gets rather tedious to write so I made a type alias.

type Fut = dyn Future<Output = Box<dyn Any>>;

Now we can refer to it as Box<Fut> instead.

If you took the closer look at Future::poll you saw it said self: Pin<&mut Self>. You can only call poll on Pin<&mut T> types. You can easily get a Pin<&mut T> from a Pin<T>. What we do is we pin the type created earlier, Pin<Box<Fut>>. Instead of calling Box::new we have to call Box::pin.

Now that we can store the future, we’re done right? Not quite, when the future finished polling we no longer want to store the future but rather it’s value, for that we have to create an enum contaning Value and Future variants.

enum FutureOrValue {

Future(Pin<Box<Fut>>),

Value(Box<dyn Any>),

}

We again use Box<dyn Any> to refer to “anything”. And with that we have basically everything. PromiseExecutor just stores a vector of FutureOrValue. Let’s move our attention to the poll method on the promise executor. We go through all the promises stored using a normal for loop. If we encounter a FutureOrValue::Future variant, we will poll it

if let FutureOrValue::Future(f) = promise {

let waker = null_waker();

let mut cx = Context::from_waker(&waker);

let result = Future::poll(f.as_mut(), &mut cx);

if let Poll::Ready(v) = result {

self.promises[key] = FutureOrValue::Value(v);

}

}

Rust futures don’t just get polled all the time, when a future wants to be polled it has to tell the async runtime it wants to be polled. This is done with the Waker type, basically a few functions that can notify the runtime. We won’t do that since Macroquad doesn’t ever call wake. null_waker() just returns a Waker that does nothing. Future take a Context type which is just a little more than a struct containing the Waker type.

With Context and a pinned future at hand, we can call poll on it. I chose to use the long variant of Future::poll for clarity. The poll call will return a value saying whether it finished, Poll::Ready(T), or not finished, Poll::Pending. If the future finished, we unwrap the value replace our promise with FutureOrValue::Value(v) instead of the FutureOrValue::Future(f) it was before. Now all that’s left is writing try_get that just checks whether the specified promise has a value and if so, return it.

And with that we are finally done with the promise executor. Using this now we can background load things without locking up the game. Now, what if Future::poll takes a while to run? The code would block and freeze up is what would happen. We have to write futures to ensure this doesn’t happen. On web, Macroquad calls into javascript with various syncronization datatypes which makes sure nothing blocks. On desktop, it blocks. That’s why I usually write a few desktop-exclusive futures manually that spawn native threads and so doesn’t block the main thread. They will continously return Poll::Pending until the thread finishes at which point it retrives the value and returns Poll::Ready.

I won’t go through it but if you’re interested, here’s what my generic “blocking function” to thread wrapper looks like. Note, web doesn’t have any threads so there’s no choice but to block.

struct WaitForBlockingFuture<T, F> {

done: Arc<AtomicBool>,

f: Option<F>,

thread: Option<JoinHandle<T>>,

}

impl<T, F> Future for WaitForBlockingFuture<T, F>

where

T: Send + 'static,

F: FnOnce() -> T + Send + 'static,

{

type Output = T;

fn poll(

mut self: Pin<&mut Self>,

_cx: &mut std::task::Context<'_>,

) -> std::task::Poll<Self::Output> {

if self.thread.is_some() {

if self.done.load(Ordering::Relaxed) {

std::task::Poll::Ready(self.thread.take().unwrap().join().unwrap())

} else {

std::task::Poll::Pending

}

} else {

#[cfg(target_family = "wasm")]

{

self.done.store(true, Ordering::Relaxed);

std::task::Poll::Ready((self.f.take().unwrap())())

}

#[cfg(not(target_family = "wasm"))]

{

let f = self.f.take().unwrap();

let done = self.done.clone();

self.thread = Some(std::thread::spawn(move || {

let v = f();

done.store(true, Ordering::Relaxed);

v

}));

std::task::Poll::Pending

}

}

}

}

Batteries Included

Wouldn’t it be nice if this was included from the start? Macroquad has an experimental system called Coroutines, it looks like this.

start_coroutine(async move {

println!("a");

next_frame().await;

println!("b");

});

your_code_here();

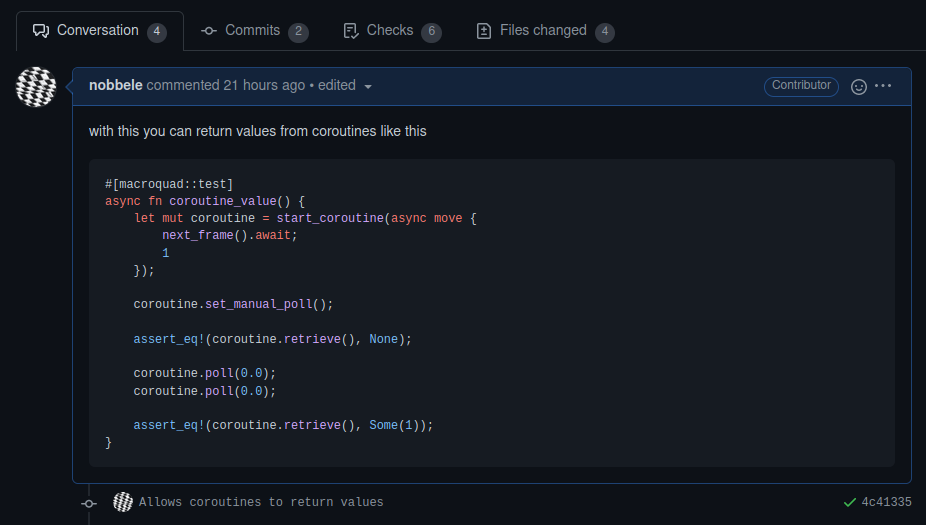

It adds the future to a coroutine context and polls it every frame. Isn’t that exactly what we want? Yes it is except for the fact that you can’t return values from it.

Now you could go ahead and create a wrapper using channels, mutexes or similar data types but then we are back at it being unnecessarily tedious to rewrite in every game, it should already be included. Since Macroquad is open-source, I went ahead and created a pull request for it.

And within a couple of hours it got merged. I will be switching over to using coroutines once Macroquad gets a new release and egui-macroquad gets an update to support it. This will make the code far easier to read and more familiar.

Conclusion

Attempting to write a production-level game in Rust has been quite the journey, it’s definitely the most ambitious project I have worked on to date. I learnt a lot about WASM, Rust’s async ecosystem, await and how it all works. So far it’s taken me a few months to make the game as smooth to use as I can. I’m sure there’s lots of things I can improve performance and code-quality wise but many hurdles comes down to my choice of supporting two targets, native and web, which requires me to write a lot of duplicate code and due to web being a bit messy to work with in general. My goal right now is to get the server side of things working properly and do a private release to test things out. Another major hurdle I left out was UI, the ecosystem there is lacking. There’s basically nothing you can use other than debug UIs such as egui (which I use for some parts), so I had to write my own which is not that great to use and has tons of UX issues but it’s the best I can do.

This part was more of a technical view into some of the major components of the game, it’s possible I will make more parts explaining things such as rulesets, replays, caching, Azusa (server), UI or the general gameplay implementation. In addition to writing the game I also continued working on osu-rs which I use to parse osu!catch beatmaps to the internal chart format, I currently don’t have any way to store them as file mostly because I haven’t gotten around to implementing it. With the addition of “rulesets”, basically game modes, you could start to classify this as a rhythm game engine maybe? but there’s only one so far, Catch The Beat.

Also name is definitely not final, I need to figure something out.